|

From a Shipmate The Perils of A New England Winter Submitted by Lawrence Rush, USS Willis A. Lee, DL4 It was a cold, gray morning in Newport on March 15, 1956, where the WILLIS A. LEE (DL-4) lay moored on the starboard side to Destroyer Pier #1 in Coddington Cove with several other destroyers moored outboard. The two-section liberty on the LEE had left only half of her crew on duty for the weekend. With the ship’s boilers cold, and on shore power, I was looking forward to a quiet two days on board, catching up on some overdue sleep and letter writing.

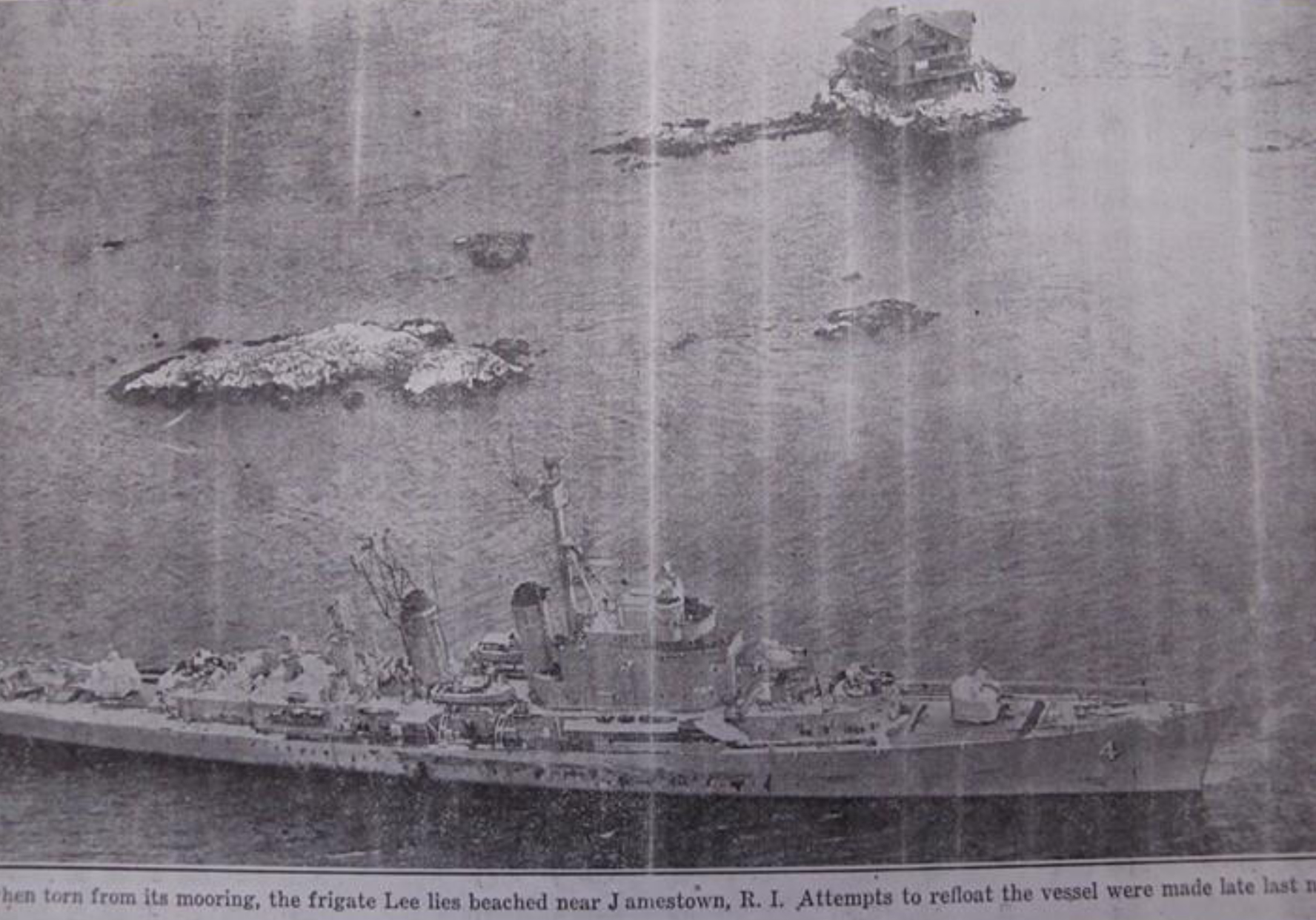

At 0107 the special sea Detail was set and moorings #1, #5 and #6, which were coated with several inches of ice, were ordered cut. After several attempts by the Boatswains Mates we, along with the outboard COOLBAUGH (DE-217), were finally freed of the pier. (Those Lee sailors who chopped the lines were left on the pier). The wind was howling in gusts up to 65 knots, snow and ice were covering everything, and visibility was essentially zero. The radar arrays were frozen in place, and we were steaming blind, praying we wouldn’t have the worst of possible accidents, a collision with another ship. Even at that, we were in better shape than the other cans, which were adrift without power. There were only 4 people in the Pilot House, including the Captain, a helmsman, and two quartermasters, and no one out on the compasses on either wing of the bridge. At 0150, the Lee passed Buoy 8A abeam to left, at 300 yards, and at 0200 she passed Rose Island Light 600 yards to Port. Here the Captain, Commander William H. Mack, ordered the Port anchor let go in 100 feet of water, with a hard sandy bottom. However, with a high profile bow and a large superstructure, and despite various Engine Order commands, the ship was set broadside by the strong winds and was driven towards shoal water on the Port Quarter. Of the 24 ships moored to the pier, six had broken their lines, including the HICKOX (DD-673), MYLES C. FOX (DD-829), and the FISKE (DD-842). When they started drifting out into the harbor, they tried to cast their anchors in an attempt to prevent being forced onto the rocks. Only the PERRY (DD-844) and the HICKOX managed to gain a little headway to get out to relatively open water. Most of the others rammed ashore in muck and sand. A Navy tug trying to help also ran aground. One later report indicated that 9 ships were loose at one time with two sets of four tied together bumping about in the bay, including the HAMMERBERG (DE-1015), GREENWOOD (DE-679), BLAIR (DE-147), HARVESON (DE-316), CALCATERRA (DER-392), RHODES (DER-384), and WOODSON (DE-359). At the height of the storm, the PRESTON (DD-795) launched a whaleboat in a vain attempt to save a sailor from the USS IRWIN (DD-794) who had slipped into the frigid water. The whaleboat was swept out of sight almost immediately, and was found the next morning on Ocean Drive, with all hands dead. The sailor from the IRWIN was swept out to sea. According to Lieutenant Commander D.D. Lewis, a public information officer, acts of heroism were “a dime a dozen” as frostbitten men, with ice covering them, strained against lines on slick decks. Most of the ships were only half manned, and were commanded by Junior Grade Lieutenants, with little experience in such a situation. Back on the LEE, after hours of fighting this wild storm, at 0210 we were all jolted with sudden lurching movements, along with a lot of screeching and groaning under the hull. Captain Mack stated instantly, "We're aground. Damage Control!". We had been blown fast on the rocks in a spot called the Dumplings, near the Jamestown shore, across from Newport. A damage control inspection showed we were in no immediate danger and at 0302, all spaces were reported as secure, and a harbor tug was lying off of the Starboard Quarter. Visibility was still poor, and the storm was logged at Condition II. On Sunday morning the exhausted crew was relieved in small groups to get some breakfast and a bit of sleep. All of the grounded ships were pulled free later in the day, when the storm had passed, the LEE being the last and the most difficult to refloat.

At 0812 on Sunday morning, March 18, the Deck Log recorded "Aground". At 0948 until 1153, various tugs (Gaspee, YTL600, YTM128) attempted to pull the ship free with heavy lines, which parted, offering no success. At 1155, all efforts ceased until the next tide. At 1635, the Lee commenced pumping fuel to lighten ship, and high pressure hoses were used to scour the bottom near the hull. Rear Admiral Virden (ComDesFlot6) and Rear Admiral Daniel (ComDesLant) boarded. At 1820, the tugs YTB364, along with the USS Sunbird , Asrie and Skylark assisted with a 2" cable attached to the gun mount 52 base, and at 2050, the Lee was afloat. The Special Sea Detail was set, and with the aid of the tugs, the damaged ship proceeded to the Anchorage Buoy M-13. The crew then had a busy week preparing to be towed to dry dock in Boston for a long period of plate and hull repairs. According to the U.S. Weather Service, this blizzard was the most powerful storm to hit New England since the 1955 hurricane. At least 40 people died in the six New England states before the storm blew itself out. With all things considered, only heroic efforts and outstanding seamanship saved the lives of many of the men involved and prevented Destroyer Flotilla 6 from destruction.

|

By noon, the wind had unexpectedly risen to 20-30 knots and Narragansett Bay was frothy with white caps. The LEE started bumping against the pier with solid dull thumps, pushed by the driving wind and the weight of the outboard ships pressing against her. By late afternoon, the wind was screeching, and it was driving a cold sleet, snow and freezing rain, which caused a slick sheet of ice to form over all of the ship’s exposed surfaces. At 2301, we were ordered to fire up the boilers as a precaution. However, since they were cold, it was going to take several hours to build up the 1200-pound pressure needed for propulsion. In the meantime, I fulfilled my duties by preparing the ship’s gyrocompasses and communications for sea duty, and standing a watch on the ship’s generators while they were fired up. While I was in the forward IC Room, I could see and hear the hull’s ribs and struts absorbing the increasing pounding the ship was taking against the pier, some of them warping, bending and cracking, even as I watched. At 2347 the bridge took a report of the longitudinal beam at Frame #72 being broken.

By noon, the wind had unexpectedly risen to 20-30 knots and Narragansett Bay was frothy with white caps. The LEE started bumping against the pier with solid dull thumps, pushed by the driving wind and the weight of the outboard ships pressing against her. By late afternoon, the wind was screeching, and it was driving a cold sleet, snow and freezing rain, which caused a slick sheet of ice to form over all of the ship’s exposed surfaces. At 2301, we were ordered to fire up the boilers as a precaution. However, since they were cold, it was going to take several hours to build up the 1200-pound pressure needed for propulsion. In the meantime, I fulfilled my duties by preparing the ship’s gyrocompasses and communications for sea duty, and standing a watch on the ship’s generators while they were fired up. While I was in the forward IC Room, I could see and hear the hull’s ribs and struts absorbing the increasing pounding the ship was taking against the pier, some of them warping, bending and cracking, even as I watched. At 2347 the bridge took a report of the longitudinal beam at Frame #72 being broken.